11 Mar The Bahá’í Response to Racial Injustice and Pursuit of Racial Unity: Part 1 (1912-1996)

The following excerpted article is from bahaiworld.bahai.org. Content ©2021 Bahá’í International Community.

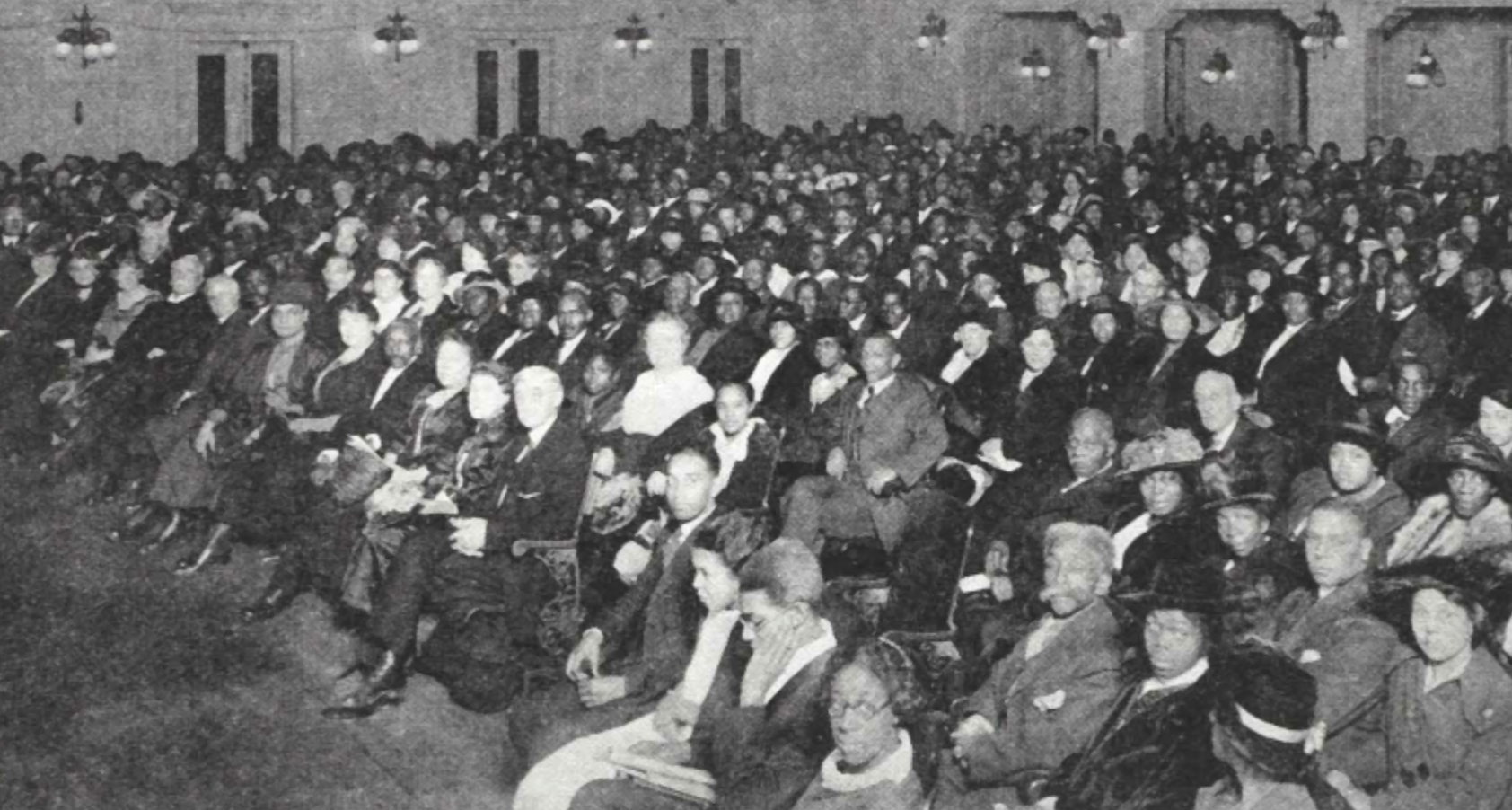

Photo: The second Bahá’í race amity convention in America, held in the auditorium of Central High School, Springfield, Massachusetts, 5-6 December 1921

BY RICHARD THOMAS

This is the first of two articles focusing on the American Bahá’í community’s efforts to bring about racial unity. This first article is a historical survey of nine decades of earnest striving and struggle in the cause of justice. A second article, to be published in the future, will focus on the profound developments in the Bahá’í world over the past twenty-five years, beginning with 1996, and explore their implications for addressing racial injustice today and in the years to come.

* * *

Once again, as the United States finds itself embroiled in racial conflicts and decades-old struggles for racial justice and racial unity, the Bahá’í community of the United States stands ready to contribute its share to the healing of the nation’s racial wounds. Neither the current racial crisis nor the current awakening is unique. Sadly, the United States has been here before.1 The American people have learned many lessons but have also forgotten other lessons about how best to solve the underlying problems facing their racially polarized society. For decades the country has seen countless efforts by brave and courageous individuals and dedicated organizations and institutions to hold back the relentless tide of racism. Many of these efforts have achieved great outcomes, but the tide has repeatedly rushed back in to test the resolve of every generation after the fall of Reconstruction, the Civil Rights Movement, and the historic election of the first African American president.2

During some of America’s worst racial crises, the Bahá’í community has joined the gallant struggle not only to hold back the tide of racism but also to build a multiracial community based on the recognition of the organic unity of the human race. Inspired by this spiritual and moral principle, the Bahá’í community, though relatively small in number and resources, has, for well over a century, sought ways to contribute to the nation’s efforts to achieve racial justice and racial unity. This has been a work in progress, humbly shared with others. It is an ongoing endeavor, one the Bahá’í community recognizes as “a long and thorny path beset with pitfalls.”3

As the Bahá’í community learns how best to build and sustain a multiracial community committed to racial justice and racial unity, it aspires to contribute to the broader struggle in society and to learn from the insights being generated by thoughtful individuals and groups working for a more just and united society.

This article provides a historical perspective on the Bahá’í community’s contribution to racial unity in the United States between 1912 and 1996. The period of 1996 to the present—a “turning point” that the Universal House of Justice characterized as setting “the Bahá’í world on a new course”4 and increasing its capacity to contribute to social progress—is still underway. During the past twenty-five years, the Bahá’í community’s capacity to contribute to humanity’s efforts to overcome deep-rooted social and spiritual ills has advanced significantly, and a subsequent article will focus on the implications of this distinctive period on the community’s ability to foster racial justice and unity.

‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Visit: Laying the Foundation for Racial Unity, 1912-1921

The Bahá’í community’s first major contribution to racial unity began in 1912 when ‘Abdul’-Bahá, the son of the Founder of the Bahá’í Faith, Bahá’u’lláh (1817-1892), visited the United States. His historic visit occurred during one of the worst periods of racial terrorism in the United States against African Americans. According to historians John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, “In the first year of the new century more than 100 Negroes were lynched and before the outbreak of World War 1 the number for the century was 1,100.” 5 In 1906, riots broke out in Atlanta, Georgia, where “whites began to attack every Negro they saw.”6 That same year, race riots also occurred in Brownsville, Texas.7 Two years later, in 1908, there were race riots in Springfield, Illinois.8 And in 1910, nation-wide race riots erupted in the wake of the heavyweight championship fight between Jack Johnson (Black) and Jim Jeffries (White) in Reno, Nevada, in July of that year.9

Racial turmoil prevailed before and after ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s visit. Yet, in this raging period of racial terrorism and conflict, He proclaimed a spiritual message of racial unity and love, and infused this message into the heart and soul of the fledgling Bahá’í community—a community still struggling to discover its role in promoting racial amity. Before His visit to the United States, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent a message to the 1911 Universal Race Conference in London in which He compared humankind to a flower garden adorned with different colors and shapes that “enhance the loveliness of each other.”10

The next year, in April, 1912, He gave a talk at Howard University, the premier African-American university in Washington D.C. A companion who kept diaries of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s Western tours and lectures wrote that whenever ‘Abdu’l-Bahá witnessed racial diversity, He was compelled to call attention to it. For example, His companion reported that, during His talk at Howard University, “here, as elsewhere, when both white and colored people were present, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá seemed happiest.” Looking over the racially mixed audience, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá had remarked: “Today I am most happy, for I see a gathering of the servants of God. I see white and black sitting together.”11

After two talks the next day, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá was visibly tired as He prepared for the third talk. He was not planning to talk long; but, here again, when he saw Blacks and Whites in the audience, He became inspired. “A meeting such as this seems like a beautiful cluster of precious jewels—pearls, rubies, diamonds, sapphires. It is a source of joy and delight. Whatever is conducive to the unity of the world of mankind is most acceptable and praiseworthy.”12 ‘Abdu’l-Bahá then went on to elaborate on the theme of racial unity to an audience of Blacks and Whites who had rarely, if ever, heard such high praise for an interracial gathering. He said to those gathered that “in the world of humanity it is wise and seemly that all the individual members should manifest unity and affinity.”13

In the midst of a period saturated with toxic racist and anti-Black language, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá offered positive racial images woven into a new language of racial unity and fellowship. He painted a picture for his interracial audience: “As I stand here tonight and look upon this assembly, I am reminded curiously of a beautiful bouquet of violets gathered together in varying colors, dark and light.”14 To still another racially mixed audience, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá commented: “In the clustered jewels of the races may the blacks be as sapphires and rubies and the whites as diamonds and pearls. The composite beauty of humanity will be witness in their unity and blending.”15

Through His words and actions, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá’í teachings on racial unity. Several examples stand out. Two Bahá’ís, Ali-Kuli Khan, the Persian charge d’affaires, and Florence Breed Khan, his wife, arranged a luncheon in ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s honor in Washington D.C. The guests were members of Washington’s social and political elite. Before the luncheon, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá sent for Louis Gregory, a lawyer and well-known African American Bahá’í. They chatted for a while, and when lunch was ready and the guests were seated, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá invited Gregory to join the luncheon. The assembled guests were no doubt surprised by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s inviting an African American to a White, upper-class social affair, but perhaps even more so by the affection and love ‘Abdu’l-Bahá showed for Gregory when He gave him the seat of honor on His right. A biographer of Louis Gregory pointed out the profound significance of ‘Abdu’l-Bahá’s action: “Gently but yet unmistakably, ‘Abdul-Bahá has assaulted the customs of a city that had been scandalized a decade earlier by President’s Roosevelt’s dinner invitation to Booker T. Washington.”16

The promotion of interracial marriage was yet another example of how ‘Abdu’l-Bahá demonstrated the Bahá’í teachings on racial unity. Many states outlawed interracial marriage or did not recognize such unions; yet, ‘Abdu’l-Bahá never wavered in his insistence that Black and White Bahá’ís should not only be unified but should also intermarry. Before his visit to the United States, He had first broached the subject in Palestine with several Western Bahá’ís and explored the sexual myths and fears at the core of American racism. His solution was to encourage interracial marriage. Once in the U.S., He demonstrated the lengths to which the American Bahá’í community should go to show its dedication to racial unity when He encouraged the marriage of Louis Gregory and an English Bahá’í, Louisa Mathew. Their marriage was the first Black-White interracial marriage that was personally encouraged by ‘Abdu’l-Bahá. This demonstration of Bahá’í teachings proved difficult for some Bahá’ís who doubted that such a union could last in a racially segregated society, but the marriage lasted until the end of the couple’s lives, nearly four decades later. Throughout this period, Louis and Louisa became a shining example of racial unity.17

Read article in its entirety at bahaiworld.bahai.org

Notes

- National Advisory Committee Report on Civil Disorders (New York: Bantam Books, 1968).

- John Hope Franklin and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., From Slavery to Freedom, 6th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, 1988), 227-38; Eoin Higgins, “The White Backlash to the Civil Rights Movement” (May 22, 2014), available at https://eoinhiggins.com/the-white-backlash-to-the-civil-rights-movement-1817ff0a9fc; David Elliot Cohen and Mark Greenberg, Obama: The Historic Front Pages (New York/London:Sterling, 2009); Adam Shatz, “How the Obama’s Presidency Provoked a White Backlash,” Los Angeles Times, October 30, 2016. Available at http://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-shatz-kerry-james-marshall-obama-20161030-story.html

- Shoghi Effendi, The Advent of Divine Justice

- Universal House of Justice, from a letter dated 10 April 2011 in Extracts from Letters Written on Behalf of the Universal House of Justice to Individual Believers in the United States on the Topic of Achieving Racial Unity (Updated Compilation 1996-2020), [7],5. Available at https://greenlakebahaischool.files.wordpress.com/2020/06/compilation-uhj-on-race-unity-1996-2020.pdf One aim of this extraordinary period from 1996 to the present has been to empower distinct populations and, indeed, the masses of humanity to take ownership of their own spiritual, intellectual, and social development. A future article will look at the impact of this latter period on the approach to the racial crisis in the United States. Recent articles on community building and approaches to building racial unity in smaller geographic spaces provide valuable insights about developments during this period.

- Franklin and Moss, 282.

- Franklin and Moss, 283.

- Franklin and Moss.

- Franklin and Moss, 285.

- Matt Reimann, “When a black fighter won ‘the fight of the century,’ race riots erupted across America.” May 25, 2017.

- G. Spiller, ed., Papers on Inter-Racial Problems Communicated to the First Universal Races Congress Held at the University of London, July 26-29, 1911. Rev. ed. (Citadel Press, 1970), 208.

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace.

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace.

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace.

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace.

- ‘Abdu’l-Bahá, The Promulgation of Universal Peace.

- Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 53.

- Gayle Morrison, To Move the World: Louis G. Gregory and the Advancement of Racial Amity in America, (Wilmette, Illinois: Bahá’í Publishing Trust, 1982), 63-72, 309-10.